Action Research in Action

In his fourth and final post in our series on bringing research into the classroom, David Dodgson gives an example of a small-scale research project he engaged in with his own learners and discusses the impact the experience had on his classroom practice.

In last month’s post, we looked at action research projects and how we could get started with them. In this post, the final one in my series about research, I will give an example of a recent small-scale action research project I conducted with one of my classes this term. This is not a comprehensive project with ground-breaking results. Instead, my intention is to show that action research does not always have to be a major project. It can be incorporated as part of our teaching practice and offer a purpose and focal point for our on-going development as language teachers.

First, I had to identify an area of focus. As ever, the inspiration for that came from my in-class experiences. Working with young learners, I do a lot of group and project work, and I find that getting them to self-regulate their efforts can be a challenge. They often focus on finishing quickly and are reluctant to revise their work (both while on task and afterwards), especially in the younger 8-10 age groups.

So, this was my initial broad focus – how can my primary learners be encouraged to check and revise the content of their project work?

Note that my question specifies not only the age but also the focus on reviewing and revising content. In an effort to encourage them to develop their language production, I decided a focus on content would be more appropriate than a focus on grammar and lexis, which is often task dependant.

In order to investigate this further, I first attended an in-house training session on Assessment for Learning. In that session, we looked at a number of activities to encourage the students to engage in self and peer reflection. It was not one of the activities we evaluated that gave me an idea to experiment with, however, but rather the way the trainer structured the session. Each group of teachers was guided through the session by a poster on the wall outlining the tasks we had to do. When we were satisfied that we had completed a stage, we ticked it off and moved onto the next one. I thought this was an interesting idea that handed over control to the groups while also providing a structure to the activity.

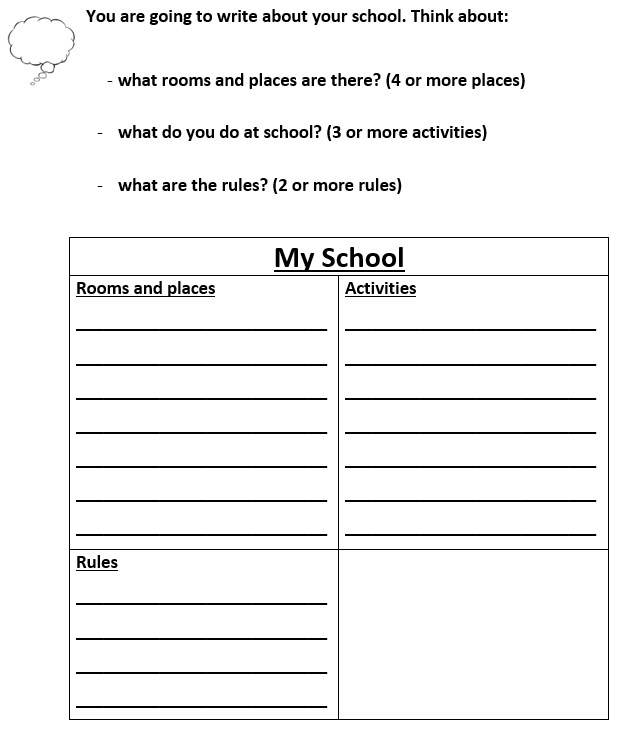

I therefore decided to take action with my primary A2 class. We had a project coming up in which they would have to design and describe a dream school. They would choose the name and the uniform, set the rules, create the timetable, and decide on the facilities. It was an exciting but potentially messy task, so I decided to use a wall chart to guide my learners through the process of planning and realising their project.

I designed a task specific wall chart to encourage them to decide on ideas for their school and assign tasks within the group for designing it. There was then a second section mapping out the stages of producing the project. I talked my class through it and instructed them to check off the tasks as they worked through them.

It had mixed success. On the one hand, it provided a road map for the groups through what was quite a lengthy period of group ‘do’ time. It meant I was able to focus on helping students with their ideas more than ensuring everyone was on task and aware of what they needed to do next. When a group declared they had ‘finished, teacher!’ I directed them back to the checklist to make sure they had completed all the stages of the project.

However, there was also some confusion with following the instructions. Some groups missed steps or did something completely different to what they (and I!) had planned. In order to understand these issues better, I needed to analyse and reflect. I approached our Head of Young Learners who reviewed the checklist poster, went through my personal reflections, and offered some constructive feedback. Together, we were able to identify that the checklist was over-doing it. Some stages were repeated across the planning and creating phases of the lesson and, in general, it was too rigid not leaving enough space for students to adapt it to their own ideas.

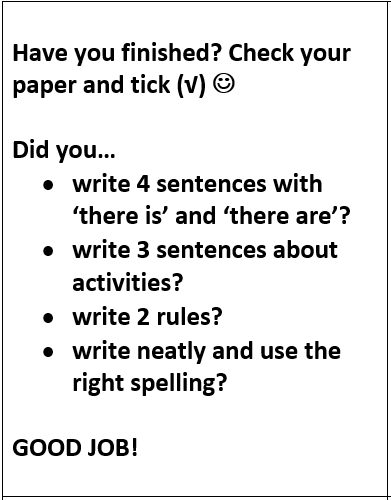

As part of my reflections, I also engaged in further investigation. This time, I consulted two books that have been mainstays of my career as a YL teacher – Teaching Young Language Learners by Annamaria Pinter and Teaching Languages to Young Learners by Lynne Cameron. Both books have excellent sections on learning strategies, which prompted me to adapt my ideas by focusing less on a checklist to refer to while on task and more on a checklist for guiding self-assessment. This would allow the learners more freedom and room to adapt when turning their ideas into a project, but it would also encourage them to revisit and revise their work after declaring “Teacher! Finished!”

Having gone through that process, it was now time to recycle. For our next project, which focused on students describing their own real-life schools, I created a planning sheet for them to brainstorm ideas and decide on task roles. They then went about creating their information posters, this time referring to their plan only to make sure they had included everything. I supplied a second sheet in the post-activity stage directing each group to return to their posters and check they had completed all the task criteria. I also invited our Head of Young Learners to observe the class to provide an objective view of the lesson to go with my own personal reflections.

This iteration went much more smoothly. The students were engaged with the task and took the time to review their work with the checklist and make some final alterations as a result. Some students did need prompting to engage fully with the task, but it is now an established part of our class routine after group and individual project work. Continuing the cycle, I have started to use similar checklists to encourage peer assessment. Ultimately, I intend to extend this action research to investigate the extent to which they can set task criteria for themselves to encourage further ownership of learning.

And what about my final stage of sharing? Well, I am sharing some initial findings here right now, and in future I will use the findings and my experiences to inform an INSETT session, and perhaps a conference talk or a more detailed article after that. This is all part of the cycle of processing, analysing, and reflecting on my findings.

As stated in the introduction to this post, this was not a comprehensive research project, simply because it did not need to be. I identified an area of interest and investigated, experimented, and reflected. I sought advice from a senior colleague and consulted experts through their book chapters and revisited and revised my project in the same way as I was encouraging my learners to do. Of course, with more time and a different focus, there could be scope for collecting more data from different teachers and different classes but in this case, I was happy to develop an area of my classroom practice and encourage my students to engage in some reflection themselves.

What are your experiences of engaging with small scale action research projects in class? Please share through the comments.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted