Considering lexical notebooks

I remember being on a bus packed with students on the way to school one morning in Japan, and I looked over the shoulder of one of them, who was engrossed in his vocabulary notebook.

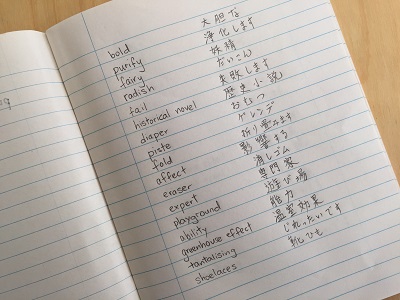

Below is a picture of how his notebook looked like to me.

Perhaps, like me, you thought, this is simply a list of random words that have no relation to each other. And this is going to make it very difficult for the student to memorise, retain and use this vocabulary.

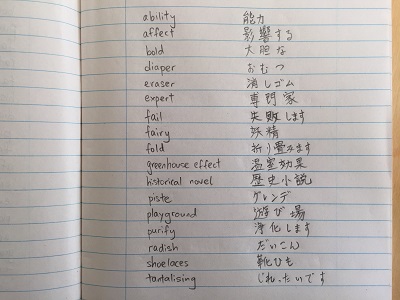

Some of you might have thought, “If we arranged them according to alphabetical order, maybe it might help.”

While the alphabetical order might appease someone like me who loves to find order in chaos, the list of words still seem as random as they did before.

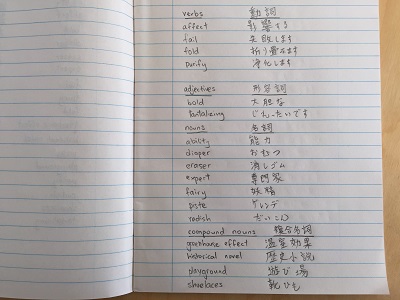

“But what if we arranged them according to their parts of speech?”

For the language enthusiast in me, this list is definitely an improvement on the previous two. At least the student will be able to know what slot in a sentence the vocabulary belongs to. But aside from that little tidbit of information, the list doesn’t actually serve to make learning any easier.

So what can we do to make vocabulary notebooks work for our students?

Let us first start by calling them lexical notebooks instead.

The term ‘vocabulary’ is often used to refer to single words of a language and could lead the learner to believe that learning to speak a language is akin to stringing individual words together to form a sentence.

And as we know, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

In both first language acquisition and second language acquisition, we often learn phrases, collocations, fixed expressions and colligations as whole units or chunks, and we fill the slots of our sentences with them, combining them to make a coherent text. (Lewis, 1993)

Getting students to call them lexical notebooks forces them to make the mental shift and to start seeing words as lexical items commonly occurring in chunks, rather than random individual words floating in a never-ending sea of unrelated vocabulary.

Here is what I consider to be important information that should be included in the notebook when recording lexis:

- The definition/meaning of the lexis.

- An example of the lexis/lexical chunk used in a sentence. Preferably demonstrating the typical context or situation that it’s found in.

- Clear indication of its part of speech (e.g. starting a verb in its ‘to-infinitve’ form can serve to indicate that it is a verb)

- Any interesting phonological features.Helpful translations

- Colligation (Does the lexis often exist with certain grammatical forms and not others? e.g. Is it often used with the perfect tense? A good dictionary should give you this information.)

- If the lexis is a phrasal verb, a clear indication as to whether it is separable or inseparable, whether it takes an object or not, and whether the object is a person or thing, etc. You can do this with an explicit ‘inseparable; person object’, or simply by inserting it into the phrasal verb itself e.g. ‘to get on with someone’

- Information about whether the lexis is an idiom or a slang, etc.

Here’s what a page of my learners’ lexical notebook might look like. (In the following case, my learner is Italian.)

| to have somebody on | prendere in giro |

| to make someone think that something is true as a joke | |

| I can’t believe you actually believed me when I said I failed my exam! I was only having you on! | |

| Informal, British slang | |

| Grammar points: Often used in the present or past continuous tense. |

We might often find that a lexical item has more than one meaning and more than one use. I wouldn’t normally recommend that learners fill their notebooks up with all the meanings of a lexical item at one go. I find that this makes learning harder as they start to confuse the different meanings and uses of the lexis.

Instead, I suggest that my learners add new lexis to their notebooks as and when they encounter them. This may be a new lexical item they learnt in class, a phrase that they saw while surfing the internet, an expression they heard in a movie, a collocation they come across again and again on Facebook, etc.

When they enter the new lexical item into their notebooks, I urge them to do some research on the lexis so as to learn more about how it is used. They could do so by searching online dictionaries or online corpora.

So, say, they have the previous entry of the phrasal verb ‘to have on’ already in their lexical notebook. They then encounter another meaning of that same phrasal verb. They would hopefully have left space after the first entry for possible additions. And this is what they might add.

| to have something on | stare indosando |

| to be wearing | |

| Did you see what he had on at the party? He had this pink shiny jacket on! | |

| Grammar points: Not usually used in the continuous tense or the passive form. | |

Notice that the grammar points for the first entry of ‘to have on’ is significantly different from the grammar points in the second entry.

So my learners have these different pages of lexical items, their use explained as clearly as possible. How then can they organise this lexis?

While some might find it useful to simply put them in alphabetical order, others might prefer to organise it according to topic or even to situation. After all, we know from schema theory that knowledge is more easily absorbed and retrieved if presented and stored in a relevant context. So the less random we make the lexis, the more easily they can be learnt and used.

Michael Lewis, in Chapter 5 of his book Implementing the Lexical Approach (2002), suggests several other ways of organizing the lexical notebook to enhance personalized learning, but ultimately the notebook belongs to the individual student, and while we can support the students by showing them the basics of what constitutes a useful lexical notebook, and we can even help them with their first few pages to get them started, but eventually, the responsibility falls on the students to continue organizing and extending their lexical notebooks in such a way that benefits them.

Bibliography

Lewis, M. (1993) The Lexical Approach. Heinle.

Lewis, M. (2002) Implementing the Lexical Approach. Heinle.

For further reading about schema theory in organizing knowledge, see this paper by Coastal Carolina University.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted