Find your online teacher self! Switching to online teaching during Covid 19

Ulla Fürstenberg and Elke Beder-Hubmann explain why it is important to get your priorities right when switching to online teaching during the Covid 19 crisis and beyond.

It is, we are told, unprecedented – the worst crisis since 1945 or since the influenza epidemic of 1918. We are certainly experiencing a situation most of us have never experienced before: strict social distancing, cities on lockdown, curfews in some areas. And yet, daily life has to go on.

For those of us who work in the public sector, this means that our classes still have to be taught. Many of us, therefore, had to transition to online teaching more or less overnight when our schools and universities were closed down – regardless of previous experience, and often without an appropriate, reliable infrastructure in place.

While we are still much better off than our freelance colleagues, who have suddenly lost all their work, let alone all the people, from doctors and nurses to lorry drivers and supermarket cashiers, who have to go out there every day and keep our society from collapsing, this is a stressful situation for us.

To make matters worse, the entire world suddenly has advice for us about teaching online. Institutions, publishers and more tech-savvy colleagues are inundating us with information about all the tools that we absolutely need in this situation – all of them, of course, foolproof and easy to use. It is hard not to feel that you owe it to your learners to use all of the tools that are available to provide the best possible learning experience.

It is not easy in such a chaotic situation, but maybe what we really have to do is take a step back and remind ourselves of some basic priorities. Yes, we should be grateful for the digital tools we have, because they allow us to continue to do our jobs in difficult circumstances – but that should ultimately be the goal: doing our jobs as efficiently as possible, not deploying as many new tools as possible. We should not let all the shiny new things that everybody is pushing on us distract us from that.

Here are some tips for teaching online in these strange times and embracing your online teacher self.

1 Invest in relationships.

Before you even think about transferring content and materials to whatever online platform you are using, you should think carefully about how you can transfer your relationships with your students to the virtual world. Instead of building completely new virtual networks, it is a good idea to think first about what you are already doing. The chances are that there are online channels of communication that you are already using with your students. Do you, perhaps, email your students regularly? Have you got a group chat with them on an online messaging service? Whatever it is, keep doing it. In a situation that is as fluid and unpredictable as the one we find ourselves in right now, your students will be grateful for a bit of continuity. You can gradually add new tools as you and they adjust to the new situation. An added advantage for you is that if, say, your first live-streamed lesson goes wrong because of a technical glitch, it will not be such a big deal, because the channels of communication that you are all used to are still open.

It is a common theme these days that we are ‘all in this together’, and this well-worn cliché applies to teaching as well. Now, more than ever, you and your students are partners in the learning process, and you can only improve your online teaching if you get feedback from them. The challenge is that online feedback cannot be as immediate as the feedback you get in the classroom. In these busy times, it is easy to fall into the habit of dropping online tasks on your students and assuming that all is well as long as they don’t complain. If you really want to know if what you are doing is working for your students, however, you have to encourage them to tell you; and they can only tell you if you are constantly and reliably present in the virtual learning landscape you share. This means taking the time to respond when they email or message you with questions, and being patient when you have to wait for them to respond to your questions.

It is also a good idea to be appreciative when they point out mistakes or alert you to technical problems with the tools you are using. They have to feel that their voice is heard, that their contribution is valued and that you are there for them if you want to recreate your classroom relationships online.

2 Get the job done.

Once you have consolidated your online relationship with your students, it’s time to focus on the content, and work out which tools can support you best in delivering the content to your students. In this phase, it is even more important than in face-to-face teaching to think very carefully about the goal of every single activity, and choose teaching tools accordingly. It is always a good idea to reflect on how you would teach a particular content point and achieve your teaching goal in the classroom. You can then think about how you are going to replicate your procedure using online tools: just as methods should always follow content in classroom teaching, online tools should always follow methods.

In some cases, the solution will be obvious. If you usually give a quick presentation and write some examples on the board to explain a grammar point, you will probably decide to film yourself or record a presentation to achieve the same effect. Other classroom procedures are trickier: for example, a ‘think–pair–share’ sequence. Here, an often overlooked factor comes into play: the technology the students have access to. Especially now, at a time when many parents are working from home, we cannot assume, for example, that younger learners always have access to the family PC. In a situation like this, it is a good idea to choose tools that work on the students’ phones.

Another point to consider is whether the teacher has to be present at every stage of an activity. This is only possible if you use some kind of videoconferencing tool, which may be tricky for younger learners to use anyway. Why not ask them to do the pairwork phase of your think–pair–share activity independently by contacting their partner on whatever channel they prefer? You can then focus on making sure there is a way they can share their results so that the whole class can benefit. If access to technology is an issue, you can always collect the results yourself on one of the channels you are used to (eg email or the online messaging services mentioned above), summarise them and distribute them back to the students. It may not be very exciting technology-wise, but it gets the job done.

3 Be yourself.

If it is important not to allow technology to dominate your relationship with your students, it is even more important not to let it quash your teacher personality. We all have our individual teaching styles. This means that a tool which is ideal for a colleague’s teaching style and personality may simply not work for you, and vice versa. A very analytically-minded teacher will not have a problem designing online work packages for a learning platform weeks in advance; a teacher who is very spontaneous may prefer a mix of tools that offer greater flexibility than a pre-designed virtual learning environment.

One of the challenges we are facing right now in our role as teachers is to find (and embrace) our online teacher self. Nobody can know, at this point, whether we will continue to teach online more than before, once it is safe for us to return to the classroom, though this seems likely. In any case, an awareness of our online teacher self is definitely something we will take with us when this crisis is over, and it may prove more valuable than mastery of any particular tool in our future teaching careers.

This brings us back to the idea of continuity mentioned above. In this volatile situation, maybe the best thing we can do for our students is to continue to be ourselves and preserve our individual approach and style. Perhaps a little stability is exactly what our students need right now, and maybe this is, above all, what we should aim to deliver online.

On the next pages, you will find some examples of Elke’s experiences of switching to teaching online.

Remote control: Elke’s example experiences

1 Ten year olds at A1 level

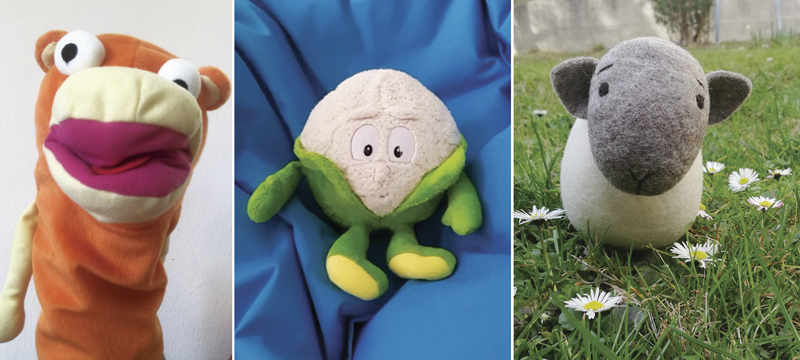

In Austrian secondary schools, we generally work with the same group of students over a long period of time (between two and eight years). This has proved particularly helpful in the current situation because it allows us to establish rapport with our students and we can, therefore, build on the familiar routine that we already follow in our face-to-face classes in our online teaching. For example, my co-teacher, Mr Frog, is a finger puppet that my ten-year-old students appreciate very much: not only does he help reluctant speakers to speak up in class, but he also plays a vital role in all kinds of grammar explanations and activities. When I left school in a rush before the lockdown, I left Mr Frog behind in the drawer of my desk, which prompted me to develop a set of creative lessons around my other finger puppet – Mr Monkey.

When it comes to content, one of the guidelines the Austrian Ministry of Education issued for ‘remote’ teaching was that we should avoid introducing too many new things during this period. For me, that meant that I needed to draw up a three-week micro-syllabus based on the present simple tense. Since all my students have mobile phones and are experts in creating videos, Mr Monkey now serves as the model who informs them about his day via recorded video messages. He also assigns tasks to them which, in teacher jargon, would be termed dictations, dictoglosses, presentations, self-correction, etc, but which have a game-like feel for the students, thanks to the presence of Mr Monkey.

While the technical skills needed on the part of the teacher for this kind of teaching include producing videos and narrating stories with storytelling tools such as Shadow Puppet Edu, the students don’t need to get used to a lot of new technology, because they use their phones automatically anyway and only have to learn how to upload their videos onto a virtual platform.

The big advantage of using stuffed animals for these kinds of tasks is that the students can relate to them, and they like to show off their own toys, too. Unlike other kinds of student-produced videos, there are no privacy issues, either. You never see the students’ faces on the screen: there is just a video or a picture of a toy they like. They enjoy trying to outdo each other in little videos in which they talk about their own stuffed animals – like Mrs Broccoli, who thinks that broccoli is incredibly boring, or Mr Alligator, who is sitting in a bed of daffodils, and never never never eats beans (for obvious reasons, which my student described very colourfully).

After a few lessons with Mr Monkey, a friend’s English-speaking daughter became Mr Monkey’s assistant and introduced Mr Sheep from Ireland as another co-teacher. Mr Sheep often eats clover, which is a word you would never read in Austrian schoolbooks at level A1, but which my students are now using happily after I sent them a picture of clover to show what it is (see below).

For me, as a teacher, this personalised method of teaching reflects what I see as my most important mission: to provide my students with a lively and creative learning environment that is both engaging and authentic. And going back to relationships, one really touching thing I have noticed is that it is often the shy students who impress me with great performances with a touch of humour when they have time to prepare and when they are not worried about speaking in front of an audience.

2 Seventeen year olds at B2 (+) level

At the other end of the range of ages and levels that I teach, there are my 17-year-old students, whose language skills are a rock-solid B2 (+) level. In the time we have been working together, they have been involved in many projects, for example my cooperation with Graz University, where they acted as school buddies for student teachers of English. My teaching has been driven throughout by their insatiable curiosity to learn and explore, and whenever I develop new materials or courses I have relied on their valuable feedback.

As they are all techno-literate, the technical side of teaching them remotely is easily explained: I only had to look at the variety of online learning platforms and learning devices that were available and decide which one to use. I appreciate all the advantages that these platforms are said to offer – for example, administrative support, which is important for students who need a gentle technical nudge sometimes, as a reminder to meet deadlines.

What has turned out to be the real challenge for me is precisely the element of creativity in my teaching that this group is used to, not in terms of technology, but in terms of performance and personality. These students enjoy critical discussions and express their opinions freely whenever they feel the urge to do so. In the classroom, I rely heavily on methods that allow them a certain degree of choice and autonomy in their learning. Incidentally, this aspect is also included in the Austrian curriculum for modern foreign languages, which explicitly encourages teachers to choose teaching methods that the students can relate to.

Here are some of the solutions I have found to transfer my real-world teaching style to remote teaching:

- My independent study list (ISL) covers a wide range of topics. It is always accessible to the students, and I update it on a regular basis, very often based on students’ recommendations. The materials that my students can choose from range from podcasts and articles to links and videos. Normally, the students choose what they want to work on, based on one-to-one meetings with me, which are similar to appraisal interviews. The work can be part of their homework assignments or serve as a basis when we flip the classroom. In remote teaching, the students have the same list, but they fill in an online form to keep track of what they have done, and they leave messages on vocaroo.com to express their opinions on the various materials they have picked from the list. Of course, there are online meetings as well that allow me to talk to the students one to one, but this class, in particular, needs a combination of personal interaction with the freedom to set their own pace and follow their interests, the way they do in the classroom.

- Pictures and videos are part of our students’ authentic online world, though this is a world that we usually don’t share with them. Since a number of international language proficiency exams, as well as our national final exam, use pictures as part of the speaking and writing prompts, it was an obvious choice to explore this option. In my regular classroom teaching, one of my favourite sites is What’s going on in this picture? in the New York Times (www.nytimes.com/column/learning-whats-going-on-in-this-picture). On further investigation, it turned out that this idea is provided by Visual Thinking Strategies (https://vtshome.org/), an American NGO which encourages critical thinking based on pictures and works of art.

In a face-to-face class, I discuss the images with my students and we always have very interesting conversations, based on their reactions and ideas. Whenever they have questions I can react spontaneously and give them background information to help them go beyond the picture. However, I struggled to replicate this kind of student-led interaction online. Even though I was able to use all kinds of streaming tools with these older students to do online teaching, this turned out not to be the same experience at all.

What we decided to do instead was to post a picture or a video and start our own chat based on this. The number of replies to a post soon made it obvious whether a particular picture resonated with the students and sparked a conversation or not, and I was able to react to this feedback accordingly, either by providing a new visual prompt if the photo was proving unsuccessful, or by encouraging the students to go deeper into the topic if there was plenty of interest in it.

- For my teacher training seminars, and to share my ideas with a broader audience, I decided to go down a different route and use Instagram instead. I am now in the process of developing an Instagram platform (you can find it at elke_beder) based on ideas for different kinds of creative speaking and writing tasks. Here is one of my tasks as an example:

I am planning to continue to add more of these kinds of tasks, even once we return to the classroom.

Ulla Fürstenberg is a Senior Lecturer in the English Department at the University of Graz, Austria, where she teaches English language and ELT Methodology classes, and a teacher trainer.

Elke Beder-Hubmann teaches English at a secondary school in Austria. She is also a teacher trainer and a lecturer in ELT Methodology at the University of Graz, Austria.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted