Flipping training: doing input outside course hours

Last year at the International House London Future of Training Conference, I posed a slightly tongue-in-cheek question to my fellow teacher trainers: What if we took away input? By input, I meant the prescribed timetable of sessions that makes up the majority of teacher training courses such as CELTA, Delta and Trinity TESOL. These sessions are designed to help the participants understand key aspects of teaching methodology and why we use them.

Lurking behind this question is the proposition that, whilst this kind of input can be effective and is often inspiring, it doesn’t always address the participants’ immediate needs or concerns about the lesson they are teaching next. In fact, the nature of a prescribed timetable means that the trainees may not yet have received the required input for their upcoming lesson, or the input was given over a week ago – which, on an intensive course, can seem like a very distant memory.

This is further complicated by the fact that, because course hours are taken up with input, the vast majority of the lesson preparation and planning is done at home. It struck me as odd that we require our trainees to analyse the language of lessons, evaluate coursebook materials and create their own lessons (all involving higher-order thinking skills) outside course hours, when during course hours we work in the lower-order zones of understanding and applying. This means that the trainees are having to make the most difficult decisions about their lessons without the support and scaffolding of their fellow trainees or the trainer.

As a result, it is the norm on intensive courses for the participants to work late into the night, only to come in the next day shattered, often anxious and unable to concentrate on input, or to realise, in the light of the input they receive, that what they have already planned needs reworking!

Is there another way to provide course participants with support at the point of need and potentially lower their stress levels?

Turning training on its head

The answer is not to take away input entirely, but to flip it to outside the course hours. The participants would then access information relevant to their own lessons and try to understand what the relevant procedure is and why we use it, in their own time. This would create the space inside the course hours to provide support tailored to individual lessons at a time when the participants need it: moving on from ‘What is …?’ and ‘Why do we …?’ to the ‘How do I …?’ of teaching procedures, techniques and activities. The lower-order thinking would be done with time to process, and the higher-order thinking would be done with people to consult.

Since that conference discussion, at International House London we have run six intensive fully-flipped CELTAs and one hybrid version. We are currently running a flipped part-time course and flipping a Delta course.

So how does flipping training work?

How it works on a CELTA

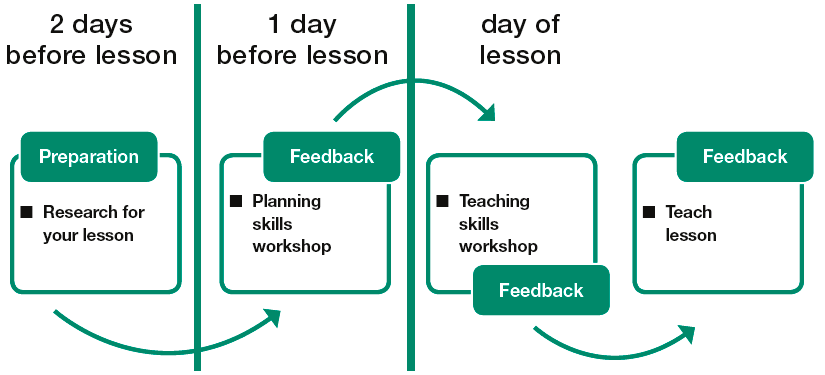

Let’s look at the overall course organisation from the perspective of a course participant. As you can see from Figure 1, they conduct guided research on their lesson, they flesh out their ideas and ask their questions in the planning skills workshop, and then have a go in the teaching skills workshop before they teach their assessed lesson. This routine continues throughout the course. There are no prescribed sessions.

Figure 1

In a course organised in this way, each trainee gets time to work on their lesson focus, plus the opportunity to ask questions and to receive feedback twice before their assessed lesson. In addition to the workshops that focus on the trainees’ lessons, we spend half an hour a day doing improvisation and play activities to work on developing teacher identity, presence and the soft skills of teaching, such as interaction.

Let’s look at the key components in more detail.

Where and how do the trainees research their lessons?

We feel it is important that the trainees should only have to go to one place to research their lessons, so we have designed a website for this purpose. Since the content is pitched at pre-service teachers, we have adopted a layman’s tone, and introduced and glossed terminology gradually. We want the content to be bite-sized and easily accessible, so we have designed short sections with mostly written content for speed of access, and this is complemented by screencasts and short video clips where appropriate. We have opted against using tasks because, whilst potentially valuable, they would be too time-consuming. Instead, we have provided a guided research worksheet to help the trainees process the information and relate it to the materials they are using in their next lesson. We also direct them to the content before and during the planning skills workshops, in teaching practice feedback and in tutorials.

What we have found

We have found that, despite our worst fears, the course participants make effective use of the flipped content to access what they need for their lessons and for their assignments. Figure 2 shows trainee feedback on their use of the website.

One trainee commented: ‘It provided valuable guidance on how to approach different types of lessons/tasks. It explained the purpose and procedures behind planning different types of lessons and techniques.’

Figure 2

Tips

Here are our top tips for using a website for flipped input:

- Set up a routine of how and when to access the site from day one, by flipping some of the input before the course starts.

- Have a checklist so that the participants tick the content they have accessed and you can track it.

- Build in responsibility by incorporating the findings of their guided research into each planning workshop.

What happens in the planning skills workshops?

We design the planning skills workshops to be responsive to the needs that the trainees identify from researching their lessons on the site. A key premise is that they should be able to cooperate together and resolve puzzles and questions they have about their lessons. To engender this, we put the trainees into mini working groups with colleagues who are focusing on similar areas – or who have, perhaps, already taught that lesson focus earlier. Once these questions are resolved, we ask the trainees to focus on one stage of their lesson, choose a planning skill to work on and cooperate to complete the task. Typical planning skills might be:

- making a whiteboard plan for that stage of the lesson;

- anticipating problems that might occur in that stage;

- writing a script for their instructions.

The key point here is that there should be a clear individual outcome from the workshop and the particular planning skill being focused on can then be shared across the group.

What we have found

We have been very pleasantly surprised by the quality of the trainees’ questioning and advice to each other from the outset. Moreover, as they research and teach their lessons, the amount of expertise in the room increases, so the trainer can increasingly take a back seat. Comments from the participants have been very positive:

‘It led to a great circulation of ideas and how I could incorporate them into my own plans. Overall great environment that I felt I could thrive in.’

‘Helping others helped clarify my own thoughts, gave me ideas for my own lessons and contributed to the feeling that we are all in this together and it was a group activity not a competition.’

Tips

Here are our top tips for planning skills workshops:

- Stage the workshops, so the participants move from critical thinking to a more goal-orientated activity – for example, making their board plan.

- Be explicit about the process, and explain to the participants that they will be problem-solving for each other.

- Resist the urge to dive in and help, even if you think the trainees are barking up the wrong tree. Instead, hold back and trust them to puzzle it out. Step in when asked or when a discussion stalls.

What happens in the teaching skills workshops?

We designed these workshops to help the trainees rehearse teaching techniques and procedures with each other before teaching real students. We set up rehearsal spaces and group the participants so that they act as learners for each other. A participant rehearses one stage of their lesson, their colleagues give feedback or alternatives, and then they have another go. The trainer facilitates this process and, when gaps arise, provides models of useful techniques. Key takeaways from the rehearsal are then shared with colleagues by, for example, the setting of maxims or criteria.

What we have found

As with the planning skills workshops, we have been pleasantly surprised by how effectively the participants work together and by the quality of the feedback or suggestions they give. It has been very apparent in teaching practice that the workshops have given the trainees the confidence to give procedures and techniques a go, and it is noticeable that having rehearsed one (perceived tricky) stage, their lessons flow more smoothly. Trainees comment favourably on the workshops:

‘They were extremely useful for visualising and getting in the right mindset and preparation for a lesson. I believe it to be one of the best things I could do before a lesson.’

‘The fresh eyes and supportive nature of my colleagues was helpful and reassuring.’

‘We would all be involved with what was the most effective way to implement tasks or teach certain points, and could draw on these for our individual practice.’

Tips

Here are our top tips for teaching skills workshops:

- Ensure that the participants come to the workshop with the handouts they are going to use in the lesson.

- Limit each teacher rehearsal to one stage of a lesson, so there is time for their colleagues to give feedback and for the teacher to have another go.

- Resist the urge to stop a rehearsal whilst a teacher is in full flow. Wait and see if the trainees can identify areas for improvement and provide alternative techniques.

What do we do in improvisation and play activities?

Teaching effectively requires presence, being present in the moment, in order to listen and respond appropriately. However, under the pressure of an observation session with a lesson plan to enact, many trainees struggle to improvise or develop these soft skills. For these reasons, we decided to integrate activities from outside ELT, mainly adapted from the world of drama, and focus on these areas.

Here is an example pairwork activity called ‘Cross purposes’:

- The participants are given cards with different situations on, such as in the cinema or at a football match. They don’t know what situation is on each other’s cards.

- Pairs take up their positions and start to improvise a dialogue.

- When they realise they are talking at cross-purposes and why, they continue the dialogue to resolve the miscommunication.

- Having done this activity, the participants reflect on how, why and when we could be at cross-purposes in a classroom setting. They then build a list of maxims to remember, in order to avoid this, but also a list of strategies for what to do if it happens.

What we have found

By integrating activities with no connection to ELT, the trainees can all be involved and feel as if they have something to contribute. We have noticed that when we then connect these activities to aspects of teaching (identity, communication skills, etc) the trainees make common sense suggestions and ask insightful questions. Improvisation and play activities foster teamwork and create a readiness to experiment. Feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, with trainees making comments such as:

‘They helped me relax and made me gain confidence, brought me closer to colleagues and created a fun atmosphere.’

‘They helped me realise that I can lose my inhibitions – that it’s good sometimes to be out of your comfort zone and that verbal is not the only form of communication. Also, they helped give us the confidence that we can improvise on the spot!’

‘I was surprised that I enjoyed them (not usually my thing) and really learnt a lot.’

Tips

Here are our top tips for improvisation and play activities:

- This may not be your kind of thing, but give it a go, because what emerges opens up the opportunities for learning.

- Provide anonymity by doing the activities in small groups.

- When the trainees are reflecting, collect their reflections and put them on the board for the others to see. You could then use this board for an observation task.

- Resist the urge to direct the trainees to your own agenda, as this tends to stall the conversation.

What difference has all this made? We have noticed a considerable difference in terms of the participants’ and trainers’ experience of the course, and in the teachers we play a part in creating. Key components of the course are built on the premise of cooperative learning. This creates a community of practice in which the trainees have the confidence in themselves and each other to question, puzzle things out, give advice and try out new things. This community starts to self-organise, the trainees take responsibility for their own and each other’s learning and so become autonomous. This experience lowers the stress levels amongst both the trainees and trainers alike. By creating these conditions, we ensure that the participants learn through their own actions and have agency, which, in turn, leads to more investment in the procedures and techniques at their disposal.

This combination of autonomy, agency and investment moves the trainees away from trying to master teaching skills simply because they are a requirement of the course, towards having the confidence to use those skills in practice. As Donald Freeman asserts, ‘knowing a particular classroom language or being able to do a specific technique only translate into actual classroom teaching to the extent that the teacher is confident of what they know and can do’. We believe that by flipping input, tailoring support to individual lessons and incorporating help at the point of need, we make our trainee teachers more confident about what they know and can do.

Freeman, D ‘Arguing for a knowledge-base in teacher education, then (1998) and now (2018)’ Language Teaching Research 2018

Melissa Lamb is a teacher and CELTA/Delta trainer, based at International House London, UK. On the rare occasion that she is not in the classroom, she spends her time collecting shells and hunting for fossils on the Jurassic coastline of southern England.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted