How many have you got? Student absence is a boon not a curse

One occasion that I have noticed tends to throw teachers off balance is when a significantly smaller number of students turn up to class than they were expecting. In the case of teenagers, this might be because a lesson coincides with a local festival, a school trip, external exams, or because it falls at the end of term when reports have already been given out and, mentally, people have started to break up for the summer or winter. Extreme weather conditions may be another cause.

In such cases, a common sight is teachers toing and froing between staffroom and class, unsure as to whether to launch into the lesson they had planned for that day – because the whole-class activities intended might not work with fewer learners; because they don’t want to use up the materials they have prepared on only a contingent of the class; or because pressing on with a regular lesson would mean putting those few students ahead, in terms of syllabus covered.

As their teacher flits about and can be heard conferring with colleagues (How many have you got? or I’ve only got three), the students sit awkwardly in their respective rooms, wondering why they came, texting their parents messages such as ‘I told you nobody was going to come, Mum!’, trying to locate other students via WhatsApp and hoping that they will not be put together with the remnants of another class, while watching the first ten or 15 minutes go by on the classroom clock.

This is a scenario that I have lived first-hand many times, but it is also one that I have managed to free myself from, because of an increasing conviction, over the years, that reduced classes like these are an absolute gift to the language teacher. It is normally the ratio of many students to just one teacher that puts a logistical ceiling on the amount of personalisation and personalised attention we are able to give our students in class. Here, that ceiling is raised a great deal higher – but making the most of it does require some adjustments.

Making the transition

The first thing we need to do when faced with a reduced class is to change our seating arrangements. If you have two or three students, there is little point in trying to teach from the board with a mountain of empty space between you and the class. You might have the students come to you and sit around your teacher’s table, or you go to them, asking the students to sit together and then shifting your chair and maybe your table over. Depending upon how the class is set up, another option may be to pull everyone into the middle of the room. With all three strategies, we are closing down distance, which sends the clear message that this is going to be a different sort of lesson. We are also sitting down and staying sitting down, rather than faffing and flapping about. This sends out the message that we are relaxed, we have a plan and we are here to stay and chat.

Having transitioned from a teacher–class set-up to an interviewer–interviewee(s) style set-up, we then need to get things underway. Just as most real-life chats that we have are not fronted with ‘Hey, let’s have a conversation now!’, this can be done without any trumpets or fanfare. If you are in the habit of making small talk with the first few students to arrive, this can be done quite naturally. However, even veteran interviewers need some back up. For this, I have a list of questions printed out and always to hand.

My own list is a resource I created some five years ago. It consists of 300 questions, divided into 20 common topics, such as neighbourhood, animals, personality and technology. These are available on my website, and a more polished version is included as a downloadable resource in my recent teens’ methodology book. Adapting that, or writing your own list from scratch, is an excellent option. When using these questions, I do often read out the topic headings and let my teenagers choose the one or two they like most, resulting in conversations like this:

But are we going to do this for the whole lesson, teacher? Just talk?

Let’s have a chat for a while and see how we get on.

But there’s only three of us. What can we do?

We can do MORE than normal. I can ask you questions and listen to you very very carefully and give you the words that you need. So what topics do you want from the ones I read out?

Mmm … Can we hear them again?

Our role as listener

Listening as a friend and listening as a language teacher are different things. As a teacher, you have no reason ever to feel guilty about making notes as your students speak. Quite the contrary: it means we are doing our job. It may not be something that feels natural to start with, but it is a skill that can be developed.

Zoning your paper

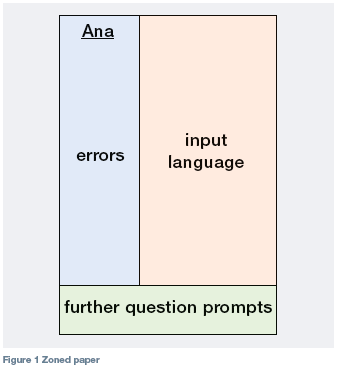

We can also help ourselves by the way we structure our notes. I recommend, for each student present, zoning a piece of paper, as shown in Figure 1.

Once you have got started, you note down on one side systematic errors that you hear. Writing them down as you hear them is easy and quick. On the other side, you jot down new language – both that which you have provided as the student is speaking, so that they can carry on, as well as additional phrases that it occurs to you may be useful as they are speaking. Then finally, at the bottom of the page, you scribble prompts for follow-up questions that spring to mind as you listen. You can then backtrack to these if and when there is a lull in the exchanges.

After every five or ten minutes of conversation, you spin the paper(s) round and correct the errors with each student and run over the input language. Some of it will naturally repeat if you remain on the same topic for another five or ten minutes.

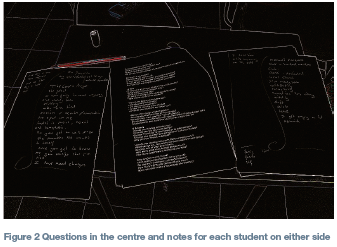

In Figure 2, I have used the edge detector feature on a photo editing programme to show you more clearly how, with two students in attendance, I had my questions in the centre and feedback from these working its way onto the zoned pieces of paper for each of the students on either side.

On this occasion, the following set of 15 questions about personality and self kept the three of us going for over an hour.

If you were an animal, what animal would you be?

What’s your favourite colour? Why?

What are you really into?

Is there anything in this world you can’t stand?

How would you describe yourself?

How many people really know you?

Are you a relaxed person?

Are you a patient person?

Is your life like you want it to be?

What do your teachers say about you?

Do you often laugh at other people?

Why do your friends enjoy being with you?

Do you know what your star sign is? (Zodiac)

Do you know what Chinese year you were born in? (dog, dragon, etc)

Which element best describes you? (earth, water, fire, air)

This system of a separate feedback sheet per student is workable for up to four students. With any more than that, you will start to run out of desk space.

And if the rest turn up?

If you have these measures at the ready, there is no need to feel any anxiety when faced with the possibility of a reduced class. I recently had only one advanced-level teenager at the start of the lesson. I was not wearing the new boots I had worn in the lesson before and explained that they had made my feet sore. I sat down and she started to tell me about a pair of Doc Martens she had. I quickly divided up a piece of paper, as described above, and at the two-minute mark already had ‘to wear them in’ and ‘softened up’ on the input language side. At that point, the rest of the class filed in – they had decided to come to class in the end rather than go trick or treating (it was Halloween night). My point here is that I was able to transition smoothly back to the regular class I had planned. Nobody had lost anything. There had been no perceived uncertainty on the part of the teacher and the student who had been first to arrive felt just as valued when it was her on her own as when her classmates turned up.

Being proactive

With the reader’s permission, I would now like to take the subject just a little further. I believe it is one-to-one teacher–student exchanges that set the tone for whole-class cooperation. We do not have to wait until their classmates are off to give individuals some undivided teacher attention. We can make space for that in a regular class. If the rest of the class is working on an exercise from their coursebook, we can ask students to come and sit with us, one by one, and listen to them for a minute as they deliver a short monologue, talk us through an anecdote or describe a picture. To this end, I try, whenever possible, to have two teacher-style chairs up at the front. On a semiotic level, I think this helps convey the notion that each student has a legitimate place sitting talking to, and getting language guidance from, their teacher as well as sitting with their peers.

The movement and the small level of facilitative tension this creates can help fuel improved language production, and if we make time at the end of the exchange to give feedback on just a couple of errors and just a couple of input items, then we have given them something to take to the next conversation they have about that topic. Being able to fragment a regular class like this and have two things going on at once requires effective task design and effective classroom management on the part of the teacher. Securing cooperation on the part of the class by convincing them of the usefulness of these short practice slots is, perhaps, the key element to success here. The ability to hone our ear to the person in front of us, cutting out the, hopefully productive, murmur in the background, is also a skill that can be developed.

Getting round them all

With my current pre-B1 group, at my students’ request, we have just had a round of one-to-one speaking with the teacher, where each student sat and described a picture for a minute and received feedback at the end (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, the rest of the class worked quietly on exercises from their activity books, allowing everyone to practise in a half-hour period.

We have also just had a round, not of one-to-one speaking with the teacher, but two-to-one speaking, where the students have sat and discussed something with a partner, again receiving feedback from me at the end of their allotted two minutes.

Obviously, we will not always be able to talk to everybody in a single lesson, and the larger the class, the more difficult this becomes. We can, however, aim to talk to each student every so often. As we have seen, seizing the chance to do so when there is a fortuitous drop in student attendance is one way. Systematically making a place for this amongst regular classwork is another, and ensures our time is more fairly meted out. In a medium-to-large class, we might try to give every student time to work through an exam-style speaking task with the teacher over the course of two or three lessons. I think one thing is for sure: in answer to the question ‘What did you do in English class today?’ we are never going to go far wrong when the answer is ‘I spoke, and the teacher listened to me’.

Chris Roland is a trainer based at ELI, a language academy in Seville, Spain. He also tutors on the Trinity Diploma course for Oxford TEFL, Barcelona. His first methodology book, Understanding Teenagers in the ELT Classroom, has recently been published by Pavilion.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted