Managing online fun

In any young learner class, be it face-to-face or remote, if you have children bouncing up and down in their chairs because they are eager to answer a question, or leaning forward on the edge of those chairs to see what you are going to write or say or show them, then you have the potential for a memorable time together. If you can structure that eagerness, giving it shape and centring activity on increased familiarity with, and production of, words and sentences in English, you have all the makings of a successful lesson.

In this article, we will look at how, whilst not needing to depart from the basic principles of learning we are familiar with, we can make the most of some characteristics of online teaching, as well as manage one or two issues that the new medium might throw up.

The elements of an online lesson

On most online platforms, we have three main elements. There is a central display area to be used as a whiteboard, to display a PowerPoint presentation or to show the pages of digital books. There is a box where the learners can see a video image of the teacher, where the teacher can see their own image (and perhaps images of the learners). Finally, there is a chat box.

Personally, I love the fact that I have a chat box. Not only does it act as a safety net for when the teacher’s spoken instructions have been forgotten (for example, we can double up by typing in the coursebook page number the learners need to turn to, as well as saying it) but it is also another opportunity to increase the learners’ exposure to the written form of words.

Providing support

No learner is ever going to enjoy a lesson if they are stressed. Nobody enjoys stress. Overloading young learners by asking them to type in too many full-length responses or unfamiliar words in the chat box will create stress. On the other hand, we still want to have our learners process as much text as possible – especially half-familiar items that they are in the process of assimilating. The following is a simple solution.

On the beach

This week I have been working on a set of beach activities with my seven and eight year olds (mostly taken from Carol Read and Mark Ormerod’s New Tiger 3) that includes building sandcastles, swimming in the sea, snorkelling, lying in the shade, putting sun cream on and playing with a bat and a ball. My learners already recognise the picture flashcards and word cards, but have not practised writing the phrases yet. Typing out these items in full would be too much for most of them, but if I type b_ilding sandcastles into the chat box, they can easily type in a one-letter response, so the exchange looks like this:

T: b_ilding sandcastles

S4: u

S9: u

S2: u

S7: u

Here, I have taken the strain off my learners, allowing them to respond quickly, which will maintain dynamism, even though this is a text-based portion of the class. By choosing my missing letters carefully, I can also draw attention to specific spelling features. Additionally, all this time, the learners are increasing their whole-word recognition of these items. In terms of differentiation, the more advanced typers in the class may decide to provide the whole word or phrase anyway, and that is fine too – in fact, I leave this option open to every learner.

Finally, I can provide an additional layer of support by prompting the learners to have their coursebooks open at the page where all the items are introduced with thumbnail pictures. In general, the best motto when it comes to online teaching with young learners is: Support, support and more support.

Daily routines

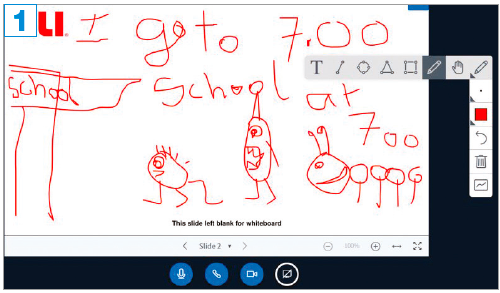

This extends to working from the central display area. In the activity shown in picture 1, the children were trying to guess the activity from my rather questionable sketches. This time, we were working on a very familiar set of phrases for daily routines.

At the end of the ‘guess the activity’ drawing, the learners also had the language they needed to produce their own sentences.

As the language was well known, I did ask for full sentences, but still provided various layers of support. Firstly, I wrote up and said the time (which was actually a primer for the end of the particular unit they were on, particular to my own context, and the reason the time appears twice). Then I began to draw. Any student who was able to guess at this point could type a full sentence into the chat box: I go to school at 7.00. In this scenario, because I was busy drawing for some time, the children had longer to prepare their sentences. In addition, those who might have struggled to put the sentence together had their faster colleagues’ offerings to use as a guide.

The support continued. When I had finished the drawing, I wrote in the sentence myself. The learners who still had not put the sentence together could now use this as guide, typing in the very same sentence that I had written, whilst I turned my attention to the chat box and acknowledged the answers that had come in so far.

Guessing games

Regular readers of ETp may remember the set of toy animals I mentioned in Issue 110. Using these online is in some ways even easier to manage, because when we hold a model up to the camera, everyone in the class can see it easily. In fact, in this aspect, online teaching has an advantage over classroom lessons as we can show any small object to all our students at once.

Guess the animal

The game shown in picture 2 is a simple guessing game from clues. The teacher enters a short text into the chat box while at the same time reading it out. For example:

It’s got wings and feathers.

It’s got an orange beak and orange feet.

The children then get to see a close-up of the model, wrapped in tinfoil or even inside a sock if you do not wish to be wasteful. They can type in the animal that they think it is.

I hope you can see that the activities so far are very close to what we might do in regular face-to-face classes and are very quick and easy to set up.

‘Guess the animal’ activity

Class mascots

Class mascots such as dolls, puppets and cuddly toys might cause squabbles when we are all in a classroom together, but when teaching remotely, nobody gets to hold them, so they can play a more prominent part in lessons. It also means that you can use that teddy bear you have had since you were four or the fluffy unicorn your best friend bought you on holiday – pieces that you might not otherwise risk taking in to school.

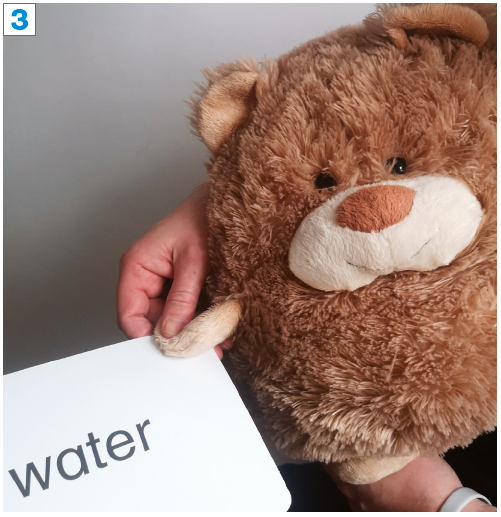

Food for Henry

In picture 3, you can see Henry, a ball of cuteness that my partner and I have been using with our students for a number of years.

Incorporating class mascots is easier online

In this activity, the learners are asked to guess what food Henry would like. They can choose anything from the current set of food items we are studying. Their script is:

Henry, do you want [+ food item]?

I then pick up the corresponding word card or flashcard, checking with the student whose turn it is that I have the right one. I offer it to Henry, who either shakes his head, or nods and takes the food item off me. Henry usually only nods his head when we are getting to the end of the set of flashcards, although occasionally he will accept the first or second item offered to him – but still be hungry, so the activity can go on – in order to avoid predictable patterns.

So what are we actually doing here? We are doing nothing more than asking our learners to try to remember the food vocabulary we have already covered (we are also giving those who can’t another look at the language). Everything else is adornment – but it is cute, low-prep adornment that will help the language stick.

Foodstuffs

One particular advantage of teaching remotely from home is that we have at our disposal the entire contents of our fridge and food cupboards. If we buy our food from the same supermarkets as our students’ parents do, which I imagine is reasonably likely, then here we have the opportunity to expand our students’ lexis on the topic, in a meaningful way, beyond the core vocabulary of our coursebook or syllabus.

Food I like/dislike

Prior to the lesson, I grab four or five items from my pantry and display them one by one to my students via the webcam. I say the word for each one and type it into the chat box. Then each student gets to respond with I like ... or I don’t like ... .

In my last lesson, I showed them mustard, gherkins, tinned fish and a chocolate in a shiny wrapper. With some flexibility, we can allow our responses to be reactive here by providing individual students with additional scripts, as and when the situation arises (most likely when they tell us in their L1). Such language might be: I don’t mind ..., I’ve never tried ..., I’m allergic to ... and I can’t stand ... .

Taking a vote

I decided to unwrap the chocolate mentioned above (see picture 4) and, to all our surprise, the surface of it had faded, as chocolate tends to do over time.

Would you eat this chocolate?

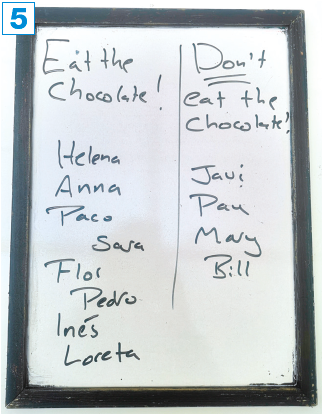

Again, we went ‘offroad’ and had an improvised lesson stage. My students each voted as to whether I should still eat the chocolate. For a vote to count, I insisted they produce a full sentence, which was either Eat the chocolate, teacher! or Don’t eat the chocolate!

I recorded their votes manually on a mini-whiteboard (see picture 5), holding it up for the children to see and, on this occasion, the consensus was that I should eat the chocolate. For the following class, I engineered a similar situation, having prepared a special ‘green egg’.

Here, old technology complements new, as we keep a record of votes on a mini-board

To make my green egg (see pictures 6, 7 and 8), I adapted a procedure that the Chinese use to make marbled tea eggs, replacing the tea with food colouring. (As a sidenote, tea has a mild antibacterial effect, whereas the food colouring solution does not, so I let the egg soak for a few hours, rather than overnight as per the traditional recipe.)

A little fun with foodstuffs

You can arouse curiosity with something your students do not see every day

Obviously this was a short novelty portion of the class, but when the students see that there is going to be a very real outcome that results from giving their opinion, they are happier to reformulate their previous one-word offerings, such as No or Yes, into full sentences, such as Eat the egg! Don’t eat the egg! or, if we want to introduce a modal, I think you should eat the egg! or I don’t think you should eat the egg!

There are a couple of key principles at work here. The first is that when the enthusiasm comes from the students, the teacher has control. The second is that for those students, giving an opinion, even if it does only involve choosing between two predetermined options, is always more engaging than being told exactly what to say. If you are not an egg person, or if you are teaching in a country where tea eggs are a common sight, and so not likely to arouse much curiosity, your students could always vote on whether or not you take a bite of a burnt piece of toast or eat a strange combination of food, such as a strawberry with peanut butter on it.

Getting away from food altogether, the students could decide what colour clothes you are going to wear in the next lesson or, indeed, if they can see each other, choose a predominant colour or specific item of clothing for everyone to wear next time.

Using chat boxes

The beauty of the chat box means that we can play our learners a YouTube clip and provide comments or questions on it without needing to pause the action. For this to work, a little priming is necessary. I say to my students: If you keep answering the questions in the chat box, I won’t stop the clip.

Preparing set messages

At some point, you may find that your chat box fills up with too much ‘noise’ – students typing in random strings of letters or chains of emojis. Much of my classroom management is done between lessons, and so when this happens, I prepare a set message for the following day, which I display in the chat box area right at the start of the lessons. This was a recent one, which I provided in both English and my learners’ L1:

I have a bank of these, saved as a Word document, so that I can copy and paste them during the lesson if a reminder is needed, all in English and in my students’ L1. I also have a series of pre-written messages addressing any technology issues that seem to recur, and I most recently used one of these set opening messages to explain how we were all going to mute our microphones during certain portions of the class according to my instructions. The particular technological issues you have will depend upon the platform you are using and your group profiles, as will the dynamic and mode in which you wish your students to employ their microphones.

Tailoring your own set messages, and having them at the ready, can save you a great deal of time and tension, and allow you to focus on enjoying your lesson and reacting to the language content of the majority of your students’ contributions, rather than getting sidetracked by individual tech problems or the one child who is going crazy on their keyboard.

***

I hope that your online classes are productive, and I hope that you manage to enjoy them along the way. It is worth remembering that if you do, then your students most probably will too.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted