'Gamify’ your classroom

Wouldn’t it be nice to have lessons engage students with the same magnetism that video games do? Though learning should be enjoyable, motivating students can be difficult, with the degree of difficulty varying according to the age group – and with teenagers generally considered the hardest. However, research focusing on motivation has come up with a field that can help: gamification, a cross-breed of psychology and the kind of loyalty programmes employed in the commercial world, but applied to other areas of life. As I studied gamification, I couldn’t help but notice that concepts like learner autonomy and enjoyment kept popping up.

What is gamification?

Essentially, gamification involves applying techniques used in video game design in non-game situations, eg earning points for performing well or completing a task. What it isn’t is playing games! I’m sure we have all played games in the classroom. Gamification is different; it turns the curriculum itself into a game.

Gamification in the classroom

The basic idea is that the students earn points for complying with the teacher’s objectives, and they can use these points later to gain rewards.

Choose your objectives

It is fundamental to decide first what kind of behaviour you wish to promote. This might be things such as completing exercises correctly individually or in groups, paying attention in class or only using English during the lesson.

Award points for compliance

Here is an example of a simple system we can use which works quickly and needs little to get started. The target behaviour is ‘only speaking English in class’ and students win points for using English as much as possible throughout the lesson, but lose them for speaking in their first language. A record is kept on the board, and the person who has most points at the end of the lesson is given a reward, eg they can choose the topic of the next class presentation.

Identify their interests

Let’s take this a step further and give our system a lick of paint by finding out what our students are interested in and using that as a theme to motivate them. Fiction and fantasy are common interests which can allow us to be someone other than ourselves. Find out what your students like – it doesn’t have to be from a game, you can use anything. Some examples might be books (eg the Harry Potter or Twilight series), games (eg Pokemon, Battlefield), movies (Toy Story, The Avengers), life (animals). It is important that you as a teacher are comfortable with whatever theme is chosen, so don’t choose sci-fi if you hate it. It is a good idea to pick general themes (eg magicians) rather than specific ones (eg Harry Potter) so that your theme stays relevant as trends change, especially if you want to use it for a long period of time.

So let’s pick a couple of themes we can use as examples: ponies and superheroes.

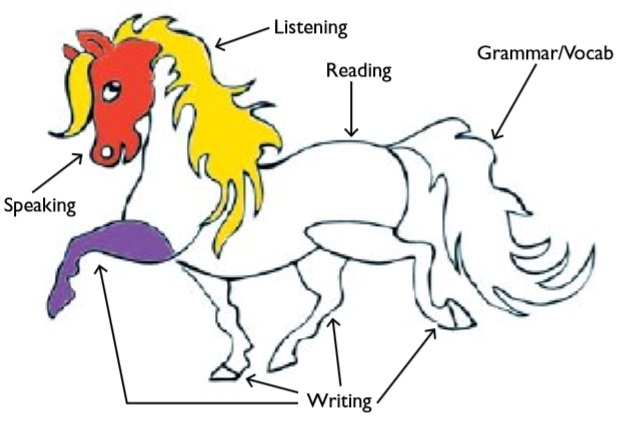

Ponies

Draw a silhouette of a pony and divide it up into sections, with each section representing one of the skills that will be assessed at the end of the course or semester, as in the example on page. 23 Make a copy for each student. When they have earned a set number of points in each area, they are allowed to colour in the relevant part, and this will give a small bonus to their final grade in that area; the brighter the colour, the bigger the bonus, eg:

Blue (or other cold colours)+0.1

Green (and warmer colours)+0.2

Red (and hot colours)+0.5

I limit these to one red, two yellow and four blue sections to choose from as they climb the points ladder. Do they choose to improve their weaknesses or boost their strengths? Guidance from the teacher is important here. The latter focuses on improving confidence by not spotlighting difficulties, and might be good for beginners or those prone to giving up. The former boosts good scores to allow the student to study the parts they really need to, without worrying quite so much about the parts they can already do.

Superheroes

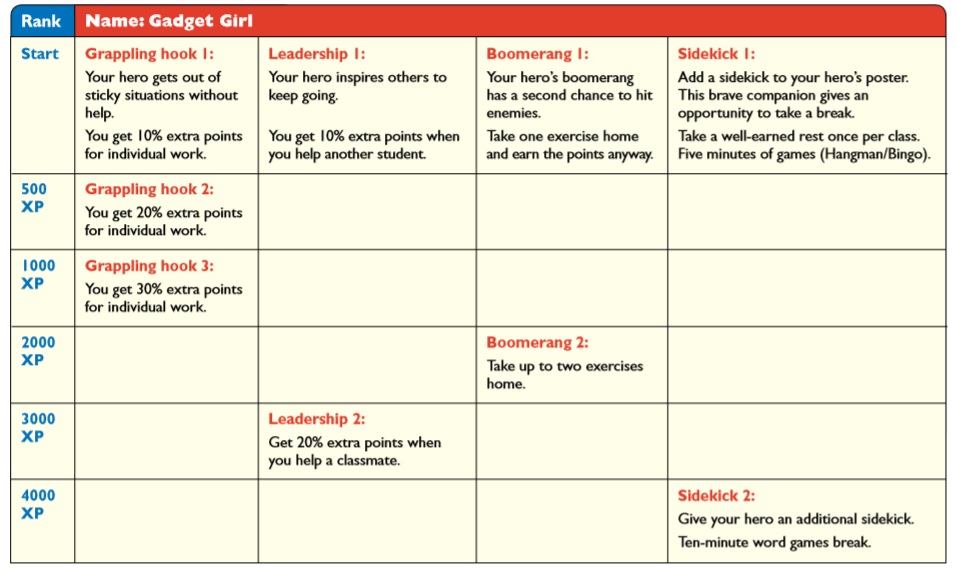

To introduce a little autonomy, get the students to make a poster of a superhero of their own design and to choose superpowers that give them bonus points. They can do this either individually or in groups that share points (keeping track of points becomes a little easier for five groups of six than for 40 individuals). You need to decide whether you want them to help each other or compete against each other.

In our example, the students (or groups) start with a number of small bonuses granted under certain conditions (see the table below). This way they can read about each bonus and see which is more to their taste. Once they earn enough points, they can upgrade a power (a maximum of two times).

The table shows a possible path taken by a group of students to upgrade at each milestone.

Each column has a power with a different focus. This class preferred to work individually most of the time and upgraded the ‘grappling hook’ bonus, which confers extra points for work they do by themselves. However, they could have easily chosen to earn more points through cooperation with a different power. This affords them meaningful choices with regards to progression. I didn’t generally award points for work which was not completed in class. The ‘boomerang’ power allowed those who were falling behind a little to earn points by finishing one exercise as homework if they ran out of time.

Finally, the ‘sidekick’ power offered a few minutes of fun and games as a reward.

If the theme of heroes is unpopular, you can modify it without changing the powers:

- Make the powers magic spells for a magician theme.

- When you create the table, have each bonus be represented by a different character like an elf, dwarf or hobbit for a fantasy theme, and change the names of the powers and their descriptions accordingly.

Let’s say the school year lasts for 40 weeks, for a total of 120 lessons per year (assuming three lessons per week). Thirty points per class should be about right. I divide up the points when I plan my lessons. For example, if the plan is to complete two pages of work and make a poster on conservation, I might assign ten points per activity.

Over the year, this will only amount to a little under 3,600 points. The 10% bonuses should make up for that a little, but we don’t want the students to reach 4,000 XP too early or they’ll be inclined to ask ‘Now what?’

Experiment a little. Let the students know that things are subject to small changes in the name of being reasonable. They usually understand justifiable changes.

Keep a visible record of progress

It is important for the students to see their progress in a concrete way. With the pony idea, have the silhouettes on posters so that the students can easily check to see how much colouring they have done and how much is still left to do. It may be easier to have one poster for each small group of students and have them share points and rewards.

The criteria for acquiring points and powers must also be transparent and visible. You might display a checklist of the unit objectives (eg Speaking: Converse in an informal situation – inviting friends to a restaurant – and in a formal situation – booking a table at a restaurant) with associated points and rewards.

Try it out for yourself! Experiment and practise. Only you know your students, so trust your instincts and, above all, have fun with this idea. Choose a simple system of points if getting bogged down in details or numbers makes your head spin. Gamification is no panacea, but an extra layer of fun can only be a good thing for everyone.

FAQs

Q: How can I use this in classes of 30 students or more? I don’t have time for all the calculations and paperwork!

A: Group students, and have the groups operate as one pony/ superhero. Or have one for the entire class. Use the opportunity to have your students debate the best options.

Q: What if my students don’t like pretending to be superheroes, or their interests are too diverse?

A: There’s no need to have any theme at all – or you can have a more neutral one, with terms like bronze, silver, gold, or coloured stars.

Q: Can they not abuse the system to find ways to ‘farm’ points for little effort?

A: They can, so beware. Keep it simple to avoid this and adjust things a little as you go. Ask the students what can be changed, and get them to help you. In general, they will be helpful.

Q: Where can I find more information on gamification?

A: Professor Werbach runs an online course that goes into far more depth than I can at www.coursera.org/course/ gamification. The games design videos by the team at Extra Creditz are also worth watching and will only take up around 15 minutes of your time:

http://penny-arcade.com/patv/episode/ gamification

http://penny-arcade.com/patv/episode/ gamifying-education

Liam Bourret-Nyffeler is a Scottish-born English teacher who has worked with students of all ages and levels. He has taught in León, Mexico, for the last four years, where he combines his passion for fun and thirst for knowledge in his classes.

Comments

Write a Comment

Comment Submitted